Grace Gould, Claire Ramey, Lucy Butcher

This 2009 “integrated recruitment campaign” from the Oregon-based athletic wear giant Nike – via the Californian advertising agency 72andSunny – “taps into the competitive spirit of young runners” and calls them to gendered action: “Join the Men vs. Women Challenge at Nikeplus.com” (72andsunny.com 2011; Hoovers.com 2011). Runners entered the competition, which launched in early March 2009 and ended in late April of the same year (won by the men), through the Nike plus (Nike+)website, where they could purchase customizable athletic shoes and clothing as well as software for tracking distances run (RunningfromZombies 2009; Nike Runing 2011). Acquisition of this software, compatible with iPods or a specially designed Nike+ SportBand, granted access to “the world’s largest running club,” a Facebook-like social network that continues to provide personalized training schedules and progress reports as well as opportunities for interacting with fellow runners. Indeed, though the “Men vs. Women Challenge” has ended, the Nike+ network is still available, and maintainsan active user base, emphasizing the running community as a whole (Nike Running).

(Click to enlarge).

Commodifying Competition

Why did Nike invoke gendered competition to lure its initial audience? The 2009 campaign speaks to resilient Euro-American constructions of gender as consisting of two discrete and heteronormative categories, at once opposed and unified, and of all gender relations as an inherent biological and psychological battle for dominance (see Pinker 1997). Thorne (1993), in her study of American children’s interactions on school playgrounds, observes that “friendly” competitive frameworks are often employed to indirectly address certain underlying tensions. “Kids use the frame of play (‘we’re only playing’; ‘it’s all fun’) as a guise for often serious, gender-related messages about sexuality and aggression,” she explains (5). This “friendly” competition speaks to cultural realities enacted in daily life, where abstract ideals of masculinity and femininity are continuously enacted through coded behaviors.

Similarly, in Nike’s ad campaign, the challenge is constantly couched in terms of play. Nike’s television ad, for example, features men and women gleefully attempting to slow each other down through childish pranks – stealing glasses, tripping each other, etc. As the more serious and competitive implications of the print ads illustrate, however, (note the intense facial expressions, the dedicated hand gestures, etc.) underlying this friendly framework is a narrative of very real battle for dominance. The “Men vs. Women Challenge” calls for young runners to prove not just their own merit, but that of their entire gender. Suddenly, the popularly circulated and aspired to notion of masculinity – couched in notions of athletic superiority and competitive aggression – is in question. What are men they if let the women beat them at their own game? Suddenly, women’s assertions of gender equality are in question – they have to prove that they are better than the men, first at running, and then in the public sphere, all the while maintaining sexed female traits. A race between men and women becomes an indirect dialogue concerning physical and social power as well as the negotiation of gendered behaviors. Combined, these ads reflect the high stakes of gender politics.

Metamessages of Ad Copy

The explicit message of the ad series is largely conveyed through text. The text is large, white, and prominently placed against dark backgrounds. Though there is not a clear sequence for the blurbs, the ad featuring the man and woman together seems a summing up of the content of the other three, since its rhetoric isn’t inherently inciting. It posits a simple binary between “men” and “women,” which Nike, like most companies and agencies, thinks to be most effective in attracting a wide pool of consumers. The word “challenge” is set off by itself spatially in an attempt to emphasize the competitive instinct that Nike wishes to instill in viewers – a drive that will bring them to the Nike Plus website to purchase special shoes needed to compete with. The initial firing up of viewers, however, is left mostly to the other three ads.

The ads featuring the single woman and the single man are interdependent: it takes two for a proper competition. However, without one ad near the other, it’s easy to jump to sexist conclusions suggested by the text. The men’s slogan, “One more thing for men to rule,” is juxtaposed with the women’s slogan, “Ladies first. Men second.” By design, both should be equally arousing and empowering, if we miss or choose to overlook the connotations of “ladies first.” This phrase references both the age of chivalry in which the ideal manly disposition determined the courteous treatment of women, and its modern adaptation that can either be used derisively or to maintain unequal gender expectations. Voicing the usually implied “men second” after the phrase is not enough to offset the fact that men fashioned it for their own prestige. “Ladies first” carries with it an unmistakable patronizing tone. Conversely, “One more thing for men to rule” points directly to men’s frequent dominance beyond the comparatively trivial Nike challenge at hand.

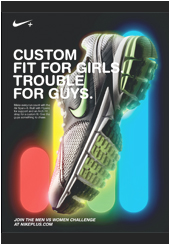

The shoe-featuring ad supports the notion that women need assistance to be “first.” Its slogan, “Custom fit for girls. Trouble for guys,” implies that only with special equipment can women hope to successfully challenge men. This Nike-enabled equality doesn’t foster equanimity between the sexes, however – it means “trouble for guys,” suggesting that otherwise men feel natural in their dominant cultural/social positions. The end of the subtext also presents a double message: “Give the guys something to chase” both restates that women aren’t worth competing against unless they have equipment to up their performance and insinuates that a woman can become more desirable socially/sexually to men by acquiring this particular shoe. Either way, the ad seeks to bolster women’s confidence by subtly undermining it first, thus establishing the need to buy Nike shoes.

Gendered Bodies

The portrayal of male and female runners in Nike’s campaign consolidates all the intricacies embedded in the language and strategies of the ad – notions of competitiveness, gender dichotomy, sexualization, domination, etc. – in visual form. Similarly to its textual counterpart, the portrayal of bodies seems to begin in the individual ads, and culminates in the ad featuring both male and female runners. As such, the “grammar” (Jhally 1995: 82) of the images differs according to intended audience, offering, in one frame, a determined and agile female athlete, in the next, a woman pursued. Just as the strategy and language of the campaign offer two levels of interpretation (play vs. battle, “egalitarian” vs. sexist), the portrayal of bodies lends itself to multiple meanings as well. These meanings, though slickly airbrushed over, are important to uncover because they reveal “the ways in which we think men and women behave,” (Jhally 1995: 81) and offer to the viewer some form of “illusory happiness” (Jhally 1995: 80), a desire conveniently commodified in sneaker form – all in the blink of an eye. It is important to investigate, then, what exactly Nike hopes to communicate visually before the reader turns the page.

In the ads featuring solo athletes, both man and woman appear to be dedicated, active agents. At first glance, their positioning is fairly equal – both stare intently at their goal, arms in motion, actively engaged in the race. Upon more detailed inspection, however, subtle differences can be observed – the man offers the photographer a sturdy thumbs-up, while the woman’s hand, though engaged, is placed daintily over her hip. While these differences certainly suggest a hierarchy of difference, it is a hierarchy obscured by the advertisements’ text. Overall, then, these two images seem to be intended to, for the most part, stand on equal footing. This is likely due to the ads’ intended audience, as each aims to motivate its respective gender to participate in the competition.

The ads featuring both male and female athlete, on the other hand, are far more problematic, and reveal the issues of battle, domination, and sexualization underlying the text and strategy. The runners’ bodies are positioned in an erotically-charged manner, hips almost touching. The man turns completely away from the camera, staring overtly at his competition. The viewer is left to determine the meaning of this gaze. Is he flirting with her? Egging her on? Pursuing her against her wishes? Several physical indicators seem to imply the existence of a an aggressive and sexual underpinning. The woman’s facial expression, for example, though similar to her individual photo, has changed. Her lips have drawn down, as if worried, whereas before her face was smooth and relaxed. Additionally, she does not return the man’s gaze, and does not seem to be enjoying his pursuit. These indicators are complicated further by the man’s overt dominance. He is featured at the center of the ad, both in front of and taller than the woman’s body. His right hand is constricted strongly, as if grasping an invisible object – a gesture invoking strength – while his left still offers a vigorous thumbs-up. The woman’s fingers, however, have curled inwards, giving her a far less agentive look.

Conclusion

Advertising campaigns like the one highlighted above trade in acculturated notions of gender and power. They reflect the ways in which these categories circulate in popular discourse, invoking and reinforcing them at the same time. Only by becoming aware of these concepts can we attempt to disamntle the structures that they support.

References

72andsunny.com. 2009. 9 April 2011. <http://www.72andsunny.com/>.

Ads of the World. March 2009. March 2011. <http://adsoftheworld.com/>.

Hoovers.com. 2011. 9 April 2011. <http://www.hoovers.com/company/NIKE_Inc/rcthci-

1.html>.

Jhally, Sut. "Image-Based Culture: Advertising in Popular Culture." Gender Race and Class in Media. Ed. Gail Dines. [S.l.]: [s.n.], 1995. Print.

Nike Running. 2011. 9 April 2011. <http://nikerunning.nike.com/nikeos/p/nikeplus/en_US>.

Pinker, Steven. “Family Values,” How the Mind Works. New York: Norton, 1997.

Runningfromzombies.com 20 April, 2009. 10 April 2011.

<http://runningfromzombies.com/2009/04/20/last-week-wc-13th-april/>.

Thorne, Barrie. Gender Play: Girls and Boys in School. New Brunswick: Rutgers University

Press, 1993.

Images taken from Ads of the World (2009), retrieved March 2011. <http://adsoftheworld.com/>.